Making the Frozen Museum

The Nunavut Arctic College (NAC) jewellery history workshop that took place between 5-15 January 2016 presents a hybrid course in which lecture is combined with hands-on studio work to support, enhance and advance learning.

In conducting this workshop, I drew upon my current experience as a postdoctoral fellow on the Making and Knowing Project at Columbia University, where we are exploring how material literacy impacts, and changes, the ways in which we "do" history - essentially, how the act of making things and physically engaging with materials opens up new ways of asking questions and seeking answers.

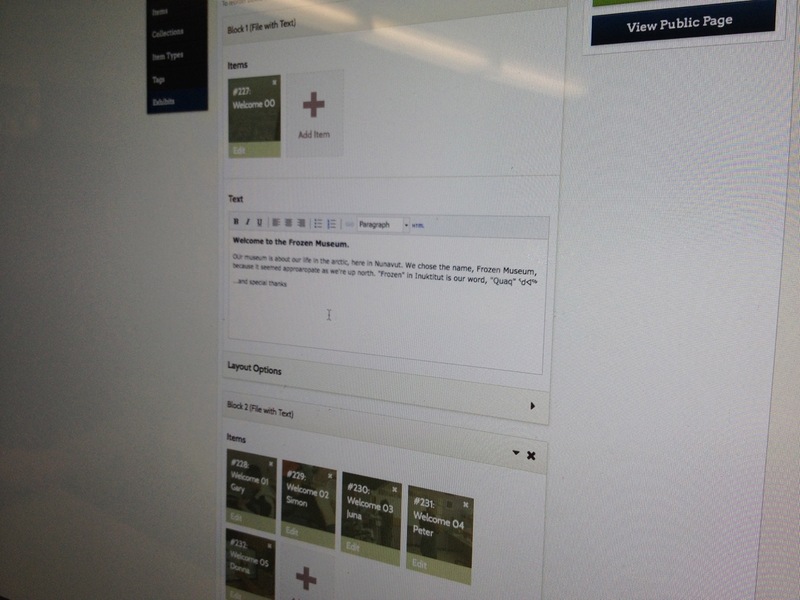

I came to NAC with a general course plan in place: to hold media-rich morning lectures that focussed on discussion about the designs, materials and technologies of jewellery from antiquity to the present day, followed by studio work in the afternoon that built upon the history lecture component in some way. I also planned from the outset to document the NAC workshop, and feature the students' work, using the online open-source content management system Omeka to create a museum exhibition of our experiences and processes. However, I did not want to dictate the assignment; instead, I elected to first meet the students and learn about their interests and skills before crafting the project, and the students had total automony in determining their museum's content.

The first class was foundational in different ways. We started with a look at photos and video of New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art (MMA) and its exhibitions about Mesopotamia, ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome that I had shot just prior to arriving in Iqaluit, and I also pulled up images of Iqaluit's local museum. We talked about the role of a museum; the students had strong opinions regarding how objects were acquired and displayed, and our discussion also encompassed thinking about the museum as a space of study and story-telling through objects. The students were fascinated by examples of hardstone seals in the MMA, which were used for millenia as modes of communication and identification. Based on this, I felt that a cylinder seal project would be the perfect medium to link lecture with studio, and I proposed that we all reconstruct our own personal cylinder seal engraved with our own narratives, and use these Arctic hardstone objets d'art to present Inuit culture to our online museum visitors - which the class, after a few days of debate, decided would be named the Frozen Museum.

Each morning began with brainstorming about our Museum before the launching into the day's lecture topic. We built a "mind map" on the classroom whiteboard, and we drew storyboards for the Omeka exhibits on sheets of paper taped together. It was interesting to watch the museum conceptually start to take shape in tandem with the physical production of our cylinder seals. Unanticipated things transpired over the next few days. I watched fascinated as Peter translated his skill in ivory carving to working with stone. During this time, Gary discovered a website that contained his family's relocation narratives, which prompted him to conduct more online searches about Resolute Bay and to question why this story is not included in how Inuit culture is presented in Canadian museums. Simon worked beside me in the studio, where he talked to me about the Arctic world as his story took shape in his hands. Juna started to ask me difficult questions about regional minerals, which prompted me to conduct an online search of my own, leading me to discover Linda Ham, Chief Geologist at the Canada-Nunavut Geoscience Office, fortuitously located two and a half blocks from the school. Linda and her colleague Serge Basso enhanced our workshop in ways I could not have planned for. Collaborating with these geologists opened up our classroom experience in profound ways, creating a synergy between science, humanities and craft practice.

The appointed hour finally came - Thursday, 14 January, 3pm - our designated time for revealing the Frozen Museum to Beata Hejnowicz, Senior Instructor of NAC's Jewellery and Metalwork Program. We pulled up the site, and I had literally just said "welcome to our museum" when the doorbell to the school rang, admitting a delegation from Ottawa who were in Iqaluit on government business, which included a visit to see the NAC facilities. The Frozen Museum suddenly had about fifteen interested visitors. On a personal note, it was deeply gratifying to see the impact that our museum had upon these first visitors, and profoundly moving to witness the students' pride in receiving validation for their ideas and work. Earlier that day, Simon had been telling me about the beneficial power of the North Star, which he had delineated upon his cylinder seal; after our museum guests left, I turned to him and noted that we'd just experienced the North Star at work. He smiled and nodded.

The next morning, when we held our last session, I restated the potential impact of the Frozen Museum to the students by pulling up a world map and pointing out to them that their stories can now be shared around the globe. This is the power of the digital realm, this ability to dissolve geographical and cultural boundaries, to spark awareness of one's place within a world-wide community, and to recognize one's self as part of a continuum.

To sum up. This hands-on jewellery history workshop was entirely collaborative, from start to finish. Each student had something particular to contribute, and each student helped to shape the direction and outcome of our capstone project, the creation of the Frozen Museum. And throughout, we were all teachers to one another. In taking dictation for the exhibits, I chose to retain the syntactical voice of each student, and I strove to be neutral in interviews in order to foreground the student’s personality and to avoid influencing the viewer’s experience.

My own story is simple. I almost didn't graduate high school (much to do with my frustration about its curricula), and my parents viewed the conferral of my doctoral degree as proof that God has a sense of humour. Before I became a historian, I was a jewellery designer and wax model maker in Toronto, Ontario, where I was trained in metal arts at George Brown College, and where Beata and I first met. I discovered history through jewellery, and my curiosity about materials and technologies has taken me down a path that I never dreamed of growing up. On this point, I received a befitting gift from the students at the end of our last class together. Simon had created an Inukshuk for me using a 19th-century inlay technique I had been describing earlier in the workshop. While Simon, Juna and Gary looked on, Peter explained that this Inukshuk is for people to know where I have been, and to guide my way back to Nunavut.